Read on Creative Frontiers.

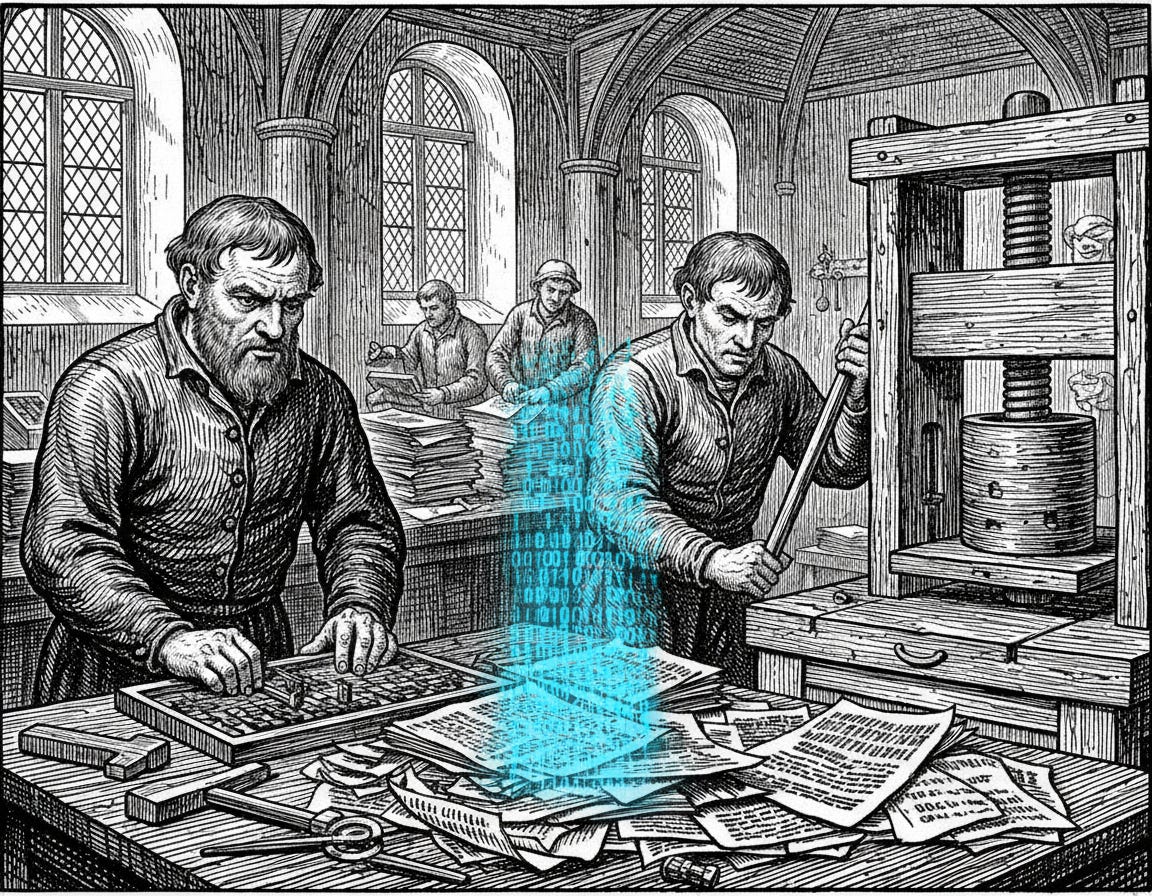

Filippo was convinced that the kids were in trouble. A flashy new machine was hijacking their attention, exposing them to risque material, and turning brains to mush, while the “tech bros” shrugged and made more. So he did what any concerned citizen would do, he wrote a letter to City Hall. Technically, it was 1474 and “City Hall” was Nicolo Marcello, Venice’s chief magistrate. The machine was the printing press. Filippo de Strata wanted it shut down.

Reading his plea, “lest the wicked should triumph,” is pure déjà vu. Ignore the courtly flattery (“may you hold sway forever… exalted as you deserve”) and the SAT words (“circumlocution”), and you’re basically at a modern Hill hearing about iPhones or ChatGPT. Same script, different nouns.

It shouldn’t be all that surprising. Human concerns don’t update as fast as the tech does. In fact, they remain pretty constant. A Benedictine monk writing five centuries ago with ink-stained fingers sounds a lot like a 2025 think tanker with a ring light. In fact, De Strata follows a classic playbook that resonates today: jobs, authenticity, and the children.

First, jobs. This is the economy. The printing press, he says, is putting “reputable writers” out of work while “utterly uncouth types of people” (printers), muscle in with their “cunning.” As a professional scribe, De Strata’s business model depended on scarcity: slow, meticulous processes. The press messed it up. “They print the stuff at such a low price that anyone and everyone procures it for himself in abundance.” Translation: scarcity for others pays my rent; abundance for others puts me out of a job.

Next, authenticity. This is sociology. Who gets to be “real”? Every scene has gate-keepers, norm-guardians that define the rules and police the border between authentic and counterfeit. De Strata draws a clear line with gusto. “True writers” wield goose-quills, printers are “drunken” and “uncultured…asses.” He explains that the work of the author is a superior art form. Writing is a “maiden with a pen” until she suffers “degradation in the brothel of the printing presses.” Then literature becomes a “harlot in print” and a “sick vice.” Tell us how you really feel, Filippo.

He also polices credentials. Printing, he worries, allows people to buy their way into expertise. For a small sum, “doctors” can be made in only three years. It’s the timeless concern that new tools compress the distance between novice and master—or create false senses of mastery. A decade ago it was weekend masterclasses, MOOCs, and Wikipedia challenging traditional passages of learning (never mind simply staying at a Holiday Inn Express last night). Today, self-publishing, Substack threads, YouTube explainers, and X let anyone speak with an expert cadence. The question though isn’t if the gate got wider, but how do we measure real mastery.

Finally, think of the children. Cheap and easily-accessible books, he warns, are vehicles of debauchery and impurity that are corrupting kids. Maybe that’s just rhetorical gasoline for his arguments to catch fire, or maybe it was a sincere pastoral concern for the next generation. As a dad who’s watched his kids disappear into a screen too often, I totally get the concerns. Either way, the “for the kids” refrain reliably clothes his economic and status concerns in civic virtue.

Unfortunately for Filippo De Strata, City Hall didn’t bite. Printers kept printing, presses multiplied, and Venice became the hottest book town in Europe. The printing press didn’t end scholarship; it multiplied the scholars. His letter didn’t stop the presses, but it left us a helpful snapshot of how we react when new tools arrive.

A 500-year-old letter is more than a curiosity, it’s a diagnostic. Objections to new tools cluster in timeless buckets: economic pain (who loses their job?), social status (who defines “real”?), and moral urgency (what about the kids?). When a fresh technology arrives, we can map the reactions and work to distinguish measurable harms from preferences for yesterday’s workflows.

De Strata wanted the future to behave like the past. Venice chose to bargain with the future, building guardrails that let abundance work for more people. The kids still need guidance. Experts still matter. But the threatening tool can become the instrument that broadens who gets to read, think, and make.